When I bought Wolfenstein: The New Order, a first-person shooter game, I didn’t think I’d end up ruminating on personality psychology for days as a result. This game has really left an impression on me like very few others have – especially for one which revolves around shooting Nazis. The tight gameplay, impactful story and visceral aesthetic all weaves together as to leave a lasting impression of a deeply impactful… if you’re the kind of gamer who thinks about such things, anyway. I’ve no doubt its critical acclaim is at least partly a result of this.

The main character in The New Order is a tough, grizzly American soldier by the name “William ‘B.J.’ Blazkowicz”. Middle name euphemisms aside, Blazkowicz slowly grows on the player as being quite significantly more than “just another military grunt” thanks to the occasional short monologue and events in the story. Ultimately, Blazkowicz becomes not a blank slate for the player to project themselves on, but rather a character developed in sync with their emotions. The story begins with a frantic aerial assault on a Nazi stronghold, ending with our character and a small team trapped by the game’s main antagonist, the aptly named “Deadhead”, a Nazi scientist. Then the game thrusts a brutal moral choice on the player, setting the scene for the unyielding brutality of its subject matter and premise: an alternate history in which the Nazis win WWII and take over the Western world. Our protagonist promptly escapes but is severely injured with shrapnel in his brain. Skipping into the future 14 years thanks to Blazkowicz being a vegetable in a Polish psych ward, the game starts in earnest when Nazis (now essentially a ubiquitous state police across Europe) massacre the hospital. Conveniently, Blazkowicz comes to his senses, and fights his way out, saving his nurse and setting up the story’s love interest. The story progresses with Blazkowicz working with a barely existent resistance, fighting against the Nazi occupation in Germany, London and even the Moon.

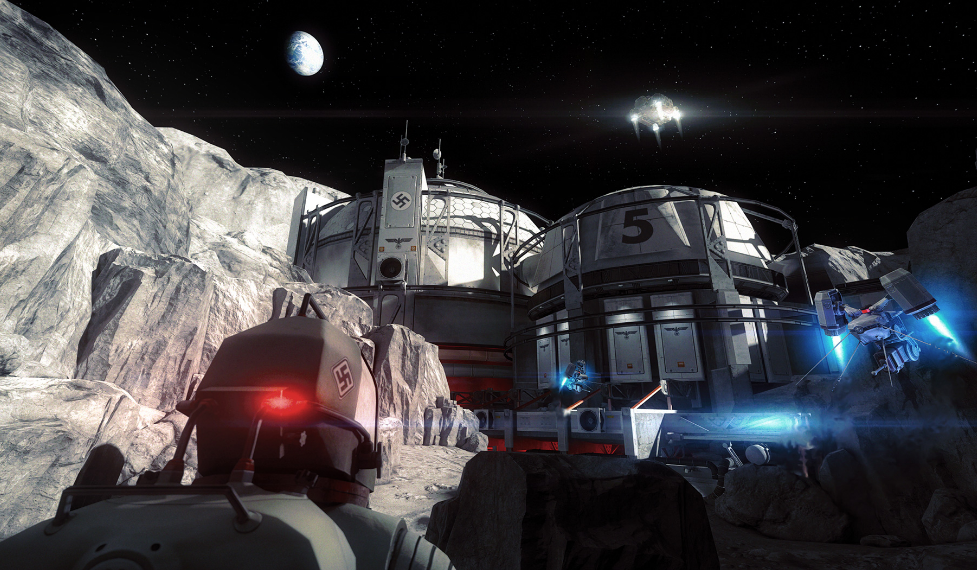

Yeah, you get to shoot space Nazis.

There’s adequate downtime in between missions, with real attention to detail in lore, characters and passing interactions which fully fledges out The New Order as a believable and compelling world. As far as video games go, Wolfenstein: The New Order gets pretty much everything correct. So instead of reviewing the game, let me describe some introspective thoughts whilst playing and after completing The New Order.

Worthy of considerable thought is the alternate history premise of the game itself. Unsurprisingly, Nazi state police are everywhere, with the general population ranging in attitude from stale ambivalence to passive displeasure. The game is set well after the German victory, so resistance is all but quelled putting the main character and his team in quite the underdog scenario. Road checkpoints are frequent, requiring citizens to carry their “papers” with them at all times. Slave labour camps are common, with one mission in particular requiring the player to go undercover in such a concentration camp, reminiscent of Auschwitz. Dialogue from and with Nazi characters indicate how the “Aryan race” is now set as a culturally superior role in society. One particular sequence on a train has another antagonist, the Nazi General Frau Engel, admiring the Aryan features of our protagonist, She plays a pernicious mind game to determine whether or not he is of “true Aryan descent”, and makes for one of the game’s more memorable non-violent sequences. This also reinforces the feeling that Nazis can essentially do whatever they want in public, much like state police in real historical examples of totalitarian regimes.

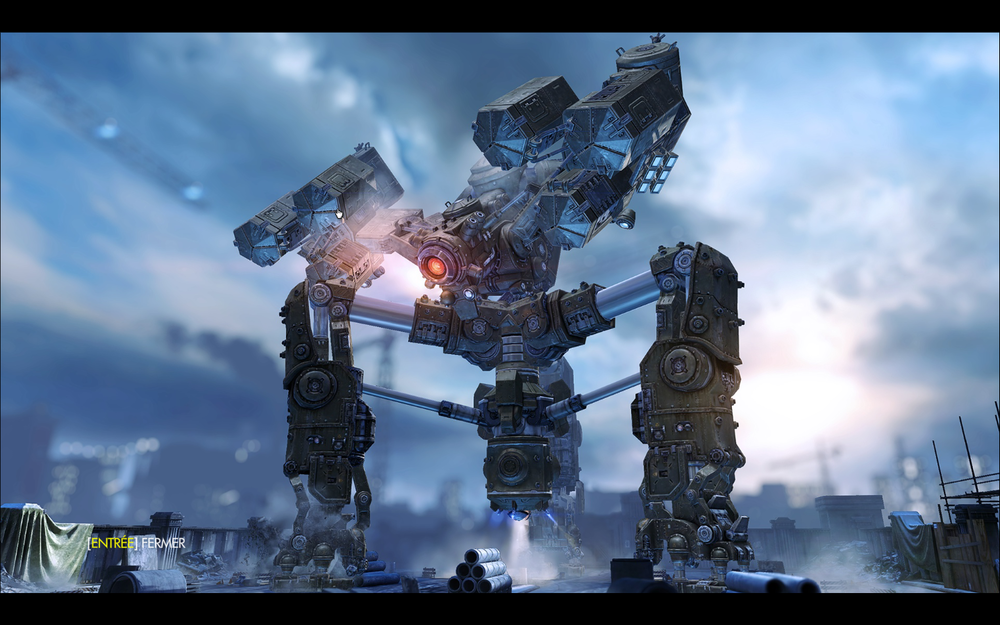

Wolfenstein’s setting frequently utilizes monolithic structures and enemies such as massive robotic dogs (Panzerhund) and Godzilla-sized robots a-la Pacific Rim. The game does a brilliant job of expressing the sheer might and oppressive force of the Nazi rule through these visuals. Two specific in-game locations that come to mind are the “London Nautica” and the Nazi Moon base.

The in-game quote noted above pretty much captures the essence of this location in Wolfenstein. Later in the game, after we return from the Moon, our protagonist fights off the robotic colossus called the “London Monitor”, outside the Nautica, pictured below.

It was the Nazi Moon base level, however, which convinced me that I had to write a blog on this game. For one thing, it’s an awesome, unabashedly fun sci-fi level. On a more analytic level however, it struck me how in this Wolfenstein‘s portrayal of a totalitarian Nazi control of the world, the lunar base is the pinnacle of the Nazi industrial war machine, combined with scientific prowess. I mean, getting to the Moon is no small feat, and neither is building a whole damn research facility there. Clearly, the Nazis are good at getting shit done.

Regardless of the realistic accuracy of such an alternate history prediction, there’s some truth to the fact that totalitarian regimes are brutally efficient when it comes to industry and military-relevant technology. We need not even look to historical totalitarian regimes – a passing consideration of the manpower, time and money which goes into modern day military R&D confirms this idea. I would muse then that Totalitarianism extends military efficiency to the entirety of industry, politics, society and scientific research. Nothing gets people off their asses quite like war and ideology.

This got me thinking on some recent personality psychology concepts which I’d come across. In particular, how Totalitarianism is in some respects, an expression of the personality factor “Orderliness” mixed with a disgust sensitivity gone mad. I’ll refer to this lecture by Jordan Peterson, in which he describes specifically this phenomenon.

In the above video, Peterson discusses a facet of personality from the Big 5 personality factors, Conscientiousness, and how it relates to Nazism and totalitarianism in general. If you get the time, I’d highly recommend watching the full lecture, as Peterson goes into significant detail on how personality and its political manifestation in Nazi Germany works.

Here are some of the main points:

– Perception is biased by our temperament

– Conscientiousness factors into two sub-traits, Industriousness and Orderliness

– Conscientiousness is the best long-term predictor of job performance

– Roughly speaking, Conscientious people sacrifice the present for the future

– Conscientious (specifically, Industrious) people are not only good at planning, but implementation too

– Industrious people find inactivity aversive

– Conscientious people strive to stabilize their environment

– Authoritarian-leaning people are high in Orderliness and Agreeableness.

– Disgust sensitivity and disgust responses evolved to detect poisonous food, but is also relevant to our perceived orderliness of the environment

– Political conservatism can be thought of as a “social immune system”

– Nazism is not so much a “descent into barbarity” as a disease of civilisation

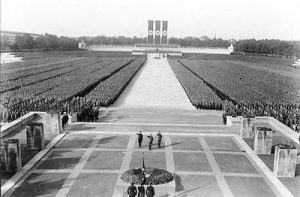

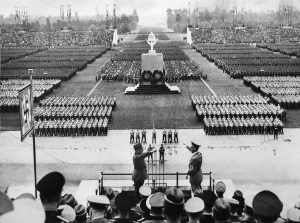

The essential point is that Nazism was Conscientiousness (specifically Orderliness) gone out of control. This isn’t just in the industrial and military side of Nazi Germany, but also the grand spectacles of order such as the Nuremberg Rallies (see below). Moreover, a disgust sensitivity which has gone out of whack with Hitler and the Nazi ideology is evident in the language used in anti-Semitic propaganda – Jews were often described as insects, or a disease.

What Wolfenstein: The New Order explores via its story, locations and aesthetics is what the world would look like if this over-the-top conscientiousness & disgust-sensitivity of Nazism was extended to our entire society. On one level, one can’t help but be both terrified and impressed by such sheer displays of orderliness and industrious efficiency. The world as presented by Wolfenstein is one of order, on a colossal magnitude. However, it is all at the expense of the individual, which hence dissolves into a cog in the machine to serve the interests of the Party or the State.

The dissolution of the individual is ironically reflected in how we often conceptualize Nazis. As with most first-person shooter games, the majority of enemies are faceless cannon-fodder, but with a game about shooting Nazis, Wolfenstein takes this to its thematic extreme. Despite this unavoidable mentality, by the game producer’s own description, The New Order does not “cartoonify” Nazis. In more than a handful of moments in-game we can eavesdrop on soldiers’ conversations about their family, complaints and the like – not that it bothers the player while slaughtering hundreds of Nazis. That being said, Wolfenstein doesn’t go as far as to give the game’s antagonists a balanced characterization which we can sympathise with. On the contrary Deathshead and Frau Engel are portrayed as archetypally perfect villains. One cut-scene near the game’s end has us observe Deathshead brutally kill Blazkowicz’s teammate in the most graphic, gory method imaginable. I’ve had my fair share of stereotypical video game ultraviolence, but this was the first time a video-game has successfully inspired the most supreme sense of disgust, shock and horror in me. It’s by this point that if they hadn’t already, the player is now in perfect psychological synchronization with Blazkowicz in feeling true, unrestricted hatred for the antagonist and Nazis overall.

Upon inner reflection however (which this game really forced me to do by its end), I got to a point of morbid understanding. Having done the Big 5 personality test several times and scoring uncomfortably high in conscientiousness myself, I can almost precisely picture myself feeling those exact emotions of disgust and hatred, but directed from the antagonist’s standpoint. This is doubly ironic thanks to the protagonist & antagonist sharing their first name: William and Wilhelm.

I’m not sure what to make of that lucid observation, nor how to articulate that feeling.

I’ll end with a few select quotes from Wolfenstein’s antagonist which should leave your skin crawling, at the very least.

-A

Terrorists. Parasites. You come to free your ilk? Well, as you drag your filthy feet across these halls, remember that you trespass against a man who built a civilization. A civilization to dwarf all others.

Prisoners. This is General Wilhelm Strasse speaking. Many of you know who I am. Many of you hate who I am. But I am also the man who can grant you freedom. I am your last chance. You see, I am a friend of the human spirit. I believe this spirit lives within you. I believe you are capable of so much more than you’ve let us know. Now…I want you to do a little exercise with me. First, take a deep breath. Then, close your eyes and look deep inside yourself. There. Inside. Is a mountain in the fog, do you see it? Way in the distance. Stretching upwards toward a blackened sky. There is a pale moon behind the mountain… and the moon would have shone its light on you… had the mountain not been there. Look further beyond the mountain… and the moon… and you’ll see the flickering stars up there in the dark void… of space. Like little diamonds. Beautiful, isn’t it? Reach up with your hands… and you can pluck one of those stars… out of the sky. Hold the star in your hand… and feel the warmth… spread throughout your body. This is what freedom feels like. This is what it will feel like… when you speak freely from the heart.

Welcome to Moon Base One. I am General Wilhelm Strasse, and I hope you will enjoy your stay. As the Minister of Advanced Research, I enjoy exploring the unknown. To penetrate the veil of uncertainty and reveal the dark secrets of the universe. There is a poem written by an anonymous poet, which goes as follows: “Dark is my heart. The greatest of secrets.” The universe is our heart, and we are just beginning to reveal its mysteries. Together we will spread the burning flame of Germania throughout the galaxy and the rest of creation. It all begins here. Sieg Heil.

Leave a Reply